Introduction

Linear regression is the next step up after correlation. Linear regression, also known as simple linear regression or bivariate linear regression, is used when we want to predict the value of a dependent variable based on the value of an independent variable. The variable we want to predict is called the dependent variable (or sometimes, the outcome variable). The variable we are using to predict the other variable's value is called the independent variable (or sometimes, the predictor variable).

SIMPLE LINEAR REGRESSION

Simple linear regression is used to predict the value of a dependent variable from the value of an independent variable.

For example, in a study of factory workers you could use simple linear regression to predict a pulmonary measure, forced vital capacity (FVC), from asbestos exposure. That is, you could determine whether increased exposure to asbestos is predictive of diminished FVC. The following SAS PROC REG code produces the simple linear regression equation for this analysis:

Notice that the MODEL statement is used to tell SAS which variables to use in the analysis. As in the ANOVA procedure the MODEL statement has the following form:

PROC REG DATA = SAS dataset <options>;

MODEL dependent (response) = regressor (predictor) <options>;

RUN ;

QUIT;

Assumptions

Confidence Intervals and Prediction Intervals

To display Confidence Interval and Prediction Interval you can include the Options CLM and CLI in your Model statement

CLI produces Confidence interval for a Individual Predicted Value

CLM produces a Confidence Interval for a Mean Predicted Value for each Individual Observation

Also add a ID Statement to print the Output Statistics

Output Statistics

The 95% CL Mean are the Intervals for the Mean Y value for a particular X value. The columns labeled 95% CL Predict are the lower and upper prediction limits. These are intervals for future value of Y at a particular value of X.

The Residual is the dependent variable minus the Predicted variable

How does regression work to enable Prediction?

Regression is a way to predict the future relationship between two random variables, given a limited set of historical information. This scatter plot represents the historical relationship between an independent variable, shown on the x-axis, and a dependent variable, shown on the y-axis.

The line that best fits the available data is the one with the smallest possible set of distances between itself and each data point. To find the line with the best fit, calculate the actual distance between each data point and every possible line through the data points.

The line with the smallest set of distances between the data points is the regression line. The trajectory of this line will best predict the future relationship between the two variables.

The concept of predictability is an important one in business. Common business uses for linear regression include forecasting sales and estimating future investment returns

Here is an Example in SAS: Initially when I saw this example I thought what is this! Then I realized this is a really a wonderful example.

Several plots are provided to help you evaluate the regression model. The following graph shows the predictive line and a confidence bands around that line. When the bands are tight around the line, it indicates better prediction, and a large band around the line indicates a less accurate prediction. In this case the confidence bands (particularly the prediction band) are fairly wide. This indicates that although CREATE is predictive of TASK, there prediction is only moderately accurate. When the R-Square is much higher, say over 0.70, the band will be tighter, and predictions will be more accurate.

Reading the Result

First look at the number of data Read and the number of data Used. If its the same it indicates that SAS detects no missing values for the variables.

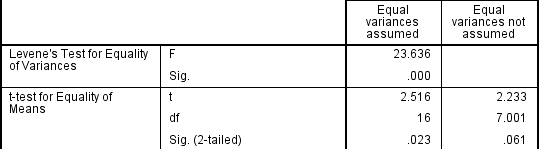

Next the Analysis of variance table displays the Overall Fit for the Model. variability explained in the reponse and the variability explained by the regression line. The Source column indicates the source of variability. Model is the between group variability that your model explains (SSM). Error is the within group variability that your Model does not explain (SSE). Corrected total is the total variability in the response.

The DF column indicates the Degrees of Freedom association with each source of variability, which are independent pieces of information for each source The Model DF is 1 because the Model has one continuous predictor term. So we are estimating one parameter beta sub1. The Corrected Total DF

n-1 which is 14 - 1 = 13. The Error DF is what is left over; it is the difference between the Total DF and the Model DF 13-1 = 12. You can think of Degrees of freedom as the number of independent pieces of information.

The Sum of Squares indicates the Amount of Variability associated with each source of variability.

Mean Square column indicated the Ratio of Model Sum of Squares divided by DF which gives us the average sum of squares of the Model.

The Mean Square Error is the variance of the population. This is calculated by the Error sum of squares by the Error DF which gives the Average Sum of Squares.

The F value is the ratio of the Mean square of the Model divided by the Mean Square for the Error. This ratio explains the variability that the regression line explains to the variability of the regression line that doesn't explain. The p-value is less than

If the p value is less the .05 and we reject the NULL Hypotheses. If the Null hypotheses is true it means the Model with CREATE is not any better than the base. However in this case the Model fit the data better than the baseline model

The third part of the displays Summary Fit measures for the Model

Root MSE - is the Square root of the Mean Square Error in the ANOVA table

Dependent Mean - Average of Response variable for all candidates

Coeff Var - Size of the Standard Deviation relative to the mean

R Square - Calculated by diving the Mean Square of the Model by the total Sum of Square. The R square value is between Zero and 1. Measures the proportion of variance observed in response that the regression line explains

What percentage of variation in the response variable does the model explain? Approximately 30%

Adjusted R Square - This is useful in Multiple Regression

The Parameter Estimates table defines the Model for the data. This provides separate estimates and Significance tests for each Model Parameter. Gives the parameter estimate for the Intercept as

2.16452 (The estimated value of TASK when CREATE is equal to zero) and the predictor variable parameter estimate as 0.06253. If the TASK increase by one unit the CREATE increase by 0.06253 units. We are interested at looking at the relationship between the TAST and CREATE. The p value is to explain the variability of response variable. Since only one predictor variable is used it is equal to the p-value of the overall test. Because the p-value 0.0396 is less than .05 there is significance in variability of TASK

Finally lets enter the results in the equation of Simple Linear Regression

Response variable = Intercept variable + Slope parameter x Predictor variable

TASK = 2.16452 + 0.06253 * CREATE (This is the estimated Regression Equation)

The Graphical Part of the Output

If you have a look at the Fit Plot the shaded area refers to the Confidence interval around the Mean. A confidence. A 95% Confidence Interval gives a range of values which is likely to include an Unknown Population parameter. This indicates that we are 95% confident our interval contains true population mean Y for a particular X. The wider the confidence interval the less precise.

The dashed lines indicate the prediction interval of the individual Observations. This means that you are 95% confident that your interval contains the new observation.

Note that by default Proc Reg displays the Model Statistics in the Plot

How do I store the results in a new dataset instead of printing it?

Use the Proc Reg to write the parameter estimates to Output dataset instead of producing the usual results and graphs. You can then use two options to the Proc Reg statement

- The NOPRINT option suppresses the normal display of regression results

- the OUTEST option creates a output dataset containing Parameter Estimates and other summary statistics from the regression model

References:

http://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/premba/analytical/s7/s7_6.cfm

http://www.stattutorials.com/SAS/TUTORIAL-PROC-REG-SIMPLE-REGRESSION.htm

Linear regression is the next step up after correlation. Linear regression, also known as simple linear regression or bivariate linear regression, is used when we want to predict the value of a dependent variable based on the value of an independent variable. The variable we want to predict is called the dependent variable (or sometimes, the outcome variable). The variable we are using to predict the other variable's value is called the independent variable (or sometimes, the predictor variable).

Types of Regression

A regression models the past relationship between variables to predict their future behavior. As an example, imagine that your company wants to understand how past advertising expenditures have related to sales in order to make future decisions about advertising. The dependent variable in this instance is sales and the independent variable is advertising expenditures.

Usually, more than one independent variable influences the dependent variable. You can imagine in the above example that sales are influenced by advertising as well as other factors, such as the number of sales representatives and the commission percentage paid to sales representatives. When one independent variable is used in a regression, it is called a simple regression; when two or more independent variables are used, it is called a multiple regression

Regression Models

Regression models can be either linear or nonlinear. A linear model assumes the relationships between variables are straight-line relationships, while a nonlinear model assumes the relationships between variables are represented by curved lines. In business you will often see the relationship between the return of an individual stock and the returns of the market modeled as a linear relationship, while the relationship between the price of an item and the demand for it is often modeled as a nonlinear relationship

Scatter Plots

Scatter plots are effective in visually identifying relationships between variables. These relationships can be expressed mathematically in terms of a correlation coefficient, which is commonly referred to as a correlation. Correlations are indices of the strength of the relationship between two variables. They can be any value from –1 to +1.

Regression Lines

Characterize the relation between the response variable and the predictor variable. he regression line is the line with the smallest possible set of distances between itself and each data point. As you can see, the regression line touches some data points, but not others. The distances of the data points from the regression line are called error terms.

Error Terms

A regression line will always contain error terms because, in reality, independent variables are never perfect predictors of the dependent variables. There are many uncontrollable factors in the business world. The error term exists because a regression model can never include all possible variables; some predictive capacity will always be absent, particularly in simple regression.

Least-squares Method

To determine the line that is as close as possible to all the datelines.

The typical procedure for finding the line of best fit is called the least-squares method. Specifically by determining the line that minimizes the sum of the squared vertical distances between the data points and the fitted line. The estimated parameters are beta hat sub zero and beta hat one - These least square estimators are often called BLUE (Best Linear Unbiased Estimators). These estimated parameters should closely approximate the true population parameters - beta sub zero and beta sub one.

In this calculation, the best fit is found by taking the difference between each data point and the line, squaring each difference, and adding the values together. The least-squares method is based upon the principle that the sum of the squared errors should be made as small as possible so the regression line has the least error. The process of finding the coefficients of a regression line by minimizing the squared error term.

In this calculation, the best fit is found by taking the difference between each data point and the line, squaring each difference, and adding the values together. The least-squares method is based upon the principle that the sum of the squared errors should be made as small as possible so the regression line has the least error. The process of finding the coefficients of a regression line by minimizing the squared error term.

Once this line is determined, it can be extended beyond the historical data to predict future levels of product awareness, given a particular level of advertising expenditure.

Measuring how well a Model Fits a data

How much better is the model that takes the predictor variable to account than a model ignores the predictor variable. To find out you can compare the Simple linear Regression Model to a Baseline Model.

Types of Variability

Explained Variability (SSM) - Is the difference between the regression line and the mean of the response variable

Unexplained (SSE) - Is the difference between the observed values and the regression lines. The error sum of squares is the amount of variability that your model fails to explains.

Total Variability - The total variability is the difference between the observed value and the mean of the response variables.

Measuring how well a Model Fits a data

How much better is the model that takes the predictor variable to account than a model ignores the predictor variable. To find out you can compare the Simple linear Regression Model to a Baseline Model.

Types of Variability

Explained Variability (SSM) - Is the difference between the regression line and the mean of the response variable

Unexplained (SSE) - Is the difference between the observed values and the regression lines. The error sum of squares is the amount of variability that your model fails to explains.

Total Variability - The total variability is the difference between the observed value and the mean of the response variables.

When do we do Simple Linear Regression?

We run simple linear regression when we want to access the relationship between two continuous variables

What SAS procedures do we use to find regression?

The REG procedure is one of many regression procedures in the SAS System. It is a general-purpose procedure for regression, while other SAS regression procedures provide more specialized applications. Other SAS/STAT procedures that perform at least one type of regression analysis are the CATMOD, GENMOD, GLM, LOGISTIC, MIXED, NLIN, ORTHOREG, PROBIT, RSREG, and TRANSREG procedures.

PROC REG provides the following capabilities:

- multiple MODEL statements

- nine model-selection methods

- interactive changes both in the model and the data used to fit the model

- linear equality restrictions on parameters

- tests of linear hypotheses and multivariate hypotheses

- collinearity diagnostics

- correlation or crossproduct input

- predicted values, residuals, studentized residuals, confidence limits, and influence statistics

- requested statistics available for output through output data sets

plots:

- plot model fit summary statistics and diagnostic statistics

- produce normal quantile-quantile (Q-Q) and probability-probability (P-P)

- plots for statistics such as residuals specify special shorthand options to plot ridge traces, confidence intervals, and prediction intervals

- display the fitted model equation, summary statistics, and reference lines on the plot

- control the graphics appearance with PLOT statement options and with global graphics statements including the TITLE, FOOTNOTE, NOTE, SYMBOL, and LEGEND statements

- paint” or highlight line-printer scatter plots

- produce partial regression leverage line-printer plots

In the simplest method, PROC REG fits the complete model that you specify. The other eight methods involve various ways of including or excluding variables from the model. You specify these

methods with the SELECTION= option in the MODEL statement.

- NONE no model selection. This is the default. The complete model specified in the MODEL statement is fit to the data.

- FORWARD forward selection. This method starts with no variables in the model and adds variables.

- BACKWARD backward elimination. This method starts with all variables in the model and deletes variables.

- STEPWISE stepwise regression. This is similar to the FORWARD method except that variables already in the model do not necessarily stay

- there.

- MAXR forward selection to fit the best one-variable model, the best two variable model, and so on. Variables are switched so that R2 is maximized.

- MINR similar to the MAXR method, except that variables are switched so that the increase in R2 from adding a variable to the model is minimized.

- RSQUARE finds a specified number of models with the highest R2 in a range of model sizes.

- ADJRSQ finds a specified number of models with the highest adjusted R2 in a range of model sizes.

- CP finds a specified number of models with the lowest Cp in a range of model sizes.

SIMPLE LINEAR REGRESSION

Simple linear regression is used to predict the value of a dependent variable from the value of an independent variable.

For example, in a study of factory workers you could use simple linear regression to predict a pulmonary measure, forced vital capacity (FVC), from asbestos exposure. That is, you could determine whether increased exposure to asbestos is predictive of diminished FVC. The following SAS PROC REG code produces the simple linear regression equation for this analysis:

PROC REG ;

MODEL FVC=ASB;

RUN ;

MODEL FVC=ASB;

RUN ;

The Simple Linear Regression Model

The regression line that SAS calculates from the data is an estimate of a theoretical line describing the relationship between the independent variable ( X ) and the dependent variable ( Y ).A simple linear regression analysis is used to develop an equation (a linear regression line) for predicting the dependent variable given a value ( x ) of the independent variable. The regression line calculated by SAS is

Y = a + bx

where a and b are the least - squares estimates of α and β.

The null hypothesis that there is no predictive linear relationship between the two variables is that the slope of the regression equation is zero. Specifically, the hypotheses are:

H 0 : β = 0

H a : β ≠ 0

H a : β ≠ 0

A low p - value for this test (say, less than 0.05) indicates significant evidence to conclude that the slope of the line is not 0 — that is, knowledge of X would be useful in predicting Y.

Suppose that a response variable Y can be predicted by a linear function of a regressor variable X. You can estimate beta sub zero, the intercept, and beta sub 1, the slope, in

for the observations i = 1; 2; : : : ; n. Fitting this model with the REG procedure requires only the following MODEL statement, where y is the outcome variable and x is the regressor variable.

proc reg;

model y=x;

run;Notice that the MODEL statement is used to tell SAS which variables to use in the analysis. As in the ANOVA procedure the MODEL statement has the following form:

MODEL dependentvar = independentvar ;

where the dependent variable ( dependentvar ) is the measure you are trying to predict

and the independent variable ( independentvar ) is your predictor.

To fit the Regression models to our data we use the REG procedure, Here is the basic syntax for the Proc Reg procedure to perform a simple linear regression and the independent variable ( independentvar ) is your predictor.

PROC REG DATA = SAS dataset <options>;

MODEL dependent (response) = regressor (predictor) <options>;

RUN ;

QUIT;

Assumptions

- The mean of Y is linearly related to X

- Errors are normally distributed with a mean of zero

- Errors have equal variances

- Errors are independent

- Remember the predictor and response variables should be continuous variables

Confidence Intervals and Prediction Intervals

To display Confidence Interval and Prediction Interval you can include the Options CLM and CLI in your Model statement

CLI produces Confidence interval for a Individual Predicted Value

CLM produces a Confidence Interval for a Mean Predicted Value for each Individual Observation

Also add a ID Statement to print the Output Statistics

Output Statistics

The 95% CL Mean are the Intervals for the Mean Y value for a particular X value. The columns labeled 95% CL Predict are the lower and upper prediction limits. These are intervals for future value of Y at a particular value of X.

The Residual is the dependent variable minus the Predicted variable

How does regression work to enable Prediction?

Regression is a way to predict the future relationship between two random variables, given a limited set of historical information. This scatter plot represents the historical relationship between an independent variable, shown on the x-axis, and a dependent variable, shown on the y-axis.

The line that best fits the available data is the one with the smallest possible set of distances between itself and each data point. To find the line with the best fit, calculate the actual distance between each data point and every possible line through the data points.

The line with the smallest set of distances between the data points is the regression line. The trajectory of this line will best predict the future relationship between the two variables.

The concept of predictability is an important one in business. Common business uses for linear regression include forecasting sales and estimating future investment returns

Here is an Example in SAS: Initially when I saw this example I thought what is this! Then I realized this is a really a wonderful example.

EXAMPLE SIMPLE LINEAR REGERSSION IN SAS

A random sample of fourteen elementary school students is selected from a school, and each student is measured on a creativity score ( X ) using a new testing instrument and on a task score ( Y ) using a standard instrument. The task score is the mean time taken to perform several hand – eye coordination tasks. Because administering the creativity test is much cheaper, the researcher wants to know if the CREATE score is a good substitute for the more expensive TASK score. The data are shown below in the following SAS code that creates a SAS data set named ART with variables SUBJECT, CREATE and TASK. Note that the SUBJECT variable is of character type so the name is followed by a dollar sign ($).

DATA ART;

INPUT SUBJECT $ CREATE TASK;

DATALINES;

AE 28 4.5

FR 35 3.9

HT 37 3.9

IO 50 6.1

DP 69 4.3

YR 84 8.8

QD 40 2.1

SW 65 5.5

DF 29 5.7

ER 42 3.0

RR 51 7.1

TG 45 7.3

EF 31 3.3

TJ 40 5.2

;

RUN;

The SAS code necessary to perform the simple linear regression analysis for this data is

ODS HTML;

ODS GRAPHICS ON;

PROC REG DATA=ART;

MODEL TASK=CREATE / CLM CLI;

TITLE “Example simple linear regression using PROC REG”;

RUN ;

ODS GRAPHICS OFF;

ODS HTML CLOSE;

QUIT;

ODS GRAPHICS ON;

PROC REG DATA=ART;

MODEL TASK=CREATE / CLM CLI;

TITLE “Example simple linear regression using PROC REG”;

RUN ;

ODS GRAPHICS OFF;

ODS HTML CLOSE;

QUIT;

If you are running SAS 9.3 or later, you can leave off the ODS statements.

“Example simple linear regression using PROC REG”

The REG Procedure

Model: MODEL1

Dependent Variable: TASK

Number of Observations

| Number of Observations Read | 14 |

|---|---|

| Number of Observations Used | 14 |

Analysis of Variance

| Analysis of Variance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Source

| DF | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F Value | Pr > F |

| Model |

1

|

13.70112

|

13.70112

|

5.33

|

0.0396

|

| Error |

12

|

30.85388

|

2.57116

| ||

| Corrected Total |

13

|

44.55500

| |||

Fit Statistic

Root MSE

|

1.60348

| R-Square |

0.3075

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Mean |

5.05000

| Adj R-Sq |

0.2498

|

| Coeff Var |

31.75213

|

Parameter Estimates

| Parameter Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | DF | Parameter Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | Pr > |t| |

| Intercept | 1 | 2.16452 | 1.32141 | 1.64 | 0.1273 |

| CREATE | 1 | 0.06253 | 0.02709 | 2.31 | 0.0396 |

Note that because you want to predict TASK from CREATE the MODEL statement is

MODEL TASK=CREATE;

Where TASK is the dependent (predicted) variable and CREATE is the independent (predictor) variable. The (partial) output from this analysis is shown next:

The Analysis of Variance table provides an overall test of the model. This test is duplicated in the Parameters table and is not shown here.

| Root MSE |

1.60348

| R-Square |

0.3075

|

| Dependent Mean |

5.05000

| Adj R-Sq |

0.2498

|

| Coeff Var |

31.75213

|

The R-Square table provides you with measures that indicate the model fit. The most commonly referenced value is R-Square which ranges from 0 to 1 and indicates the proportion of variance explained in the model. The closer R-Square is to 1, the better the model fit. According to Cohen (1988), an R-Square of 0.31 indicates a large effect size, which is an indication that CREATE is predictive of TASK.

Parameter Estimates

| |||||

| Variable |

DF

|

Parameter

Estimate

|

Standard

Error

|

t Value

|

Pr > |t|

|

| Intercept |

1

|

2.16452

|

1.32141

|

1.64

|

0.1273

|

| CREATE |

1

|

0.06253

|

0.02709

|

2.31

|

0.0396

|

The Parameter Estimate table provides the coefficients for the regression equation, and a test of the null hypothesis that the slope is zero. (p=0.0396 indicates that you would reject the hull hypothesis and conclude that the slope is not zero.)

In this example, the predictive equation (using the estimates in the above table) is

TASK = 2.126452 + CREATE * 0.06253

Thus, if you have a value for CREATE, you can put that value into the equation and predict TASK.

The question is, how good is the prediction? Several plots are provided to help you evaluate the regression model. The following graph shows the predictive line and a confidence bands around that line. When the bands are tight around the line, it indicates better prediction, and a large band around the line indicates a less accurate prediction. In this case the confidence bands (particularly the prediction band) are fairly wide. This indicates that although CREATE is predictive of TASK, there prediction is only moderately accurate. When the R-Square is much higher, say over 0.70, the band will be tighter, and predictions will be more accurate.

Reference: Jacob Cohen (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (second ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Reading the Result

First look at the number of data Read and the number of data Used. If its the same it indicates that SAS detects no missing values for the variables.

Next the Analysis of variance table displays the Overall Fit for the Model. variability explained in the reponse and the variability explained by the regression line. The Source column indicates the source of variability. Model is the between group variability that your model explains (SSM). Error is the within group variability that your Model does not explain (SSE). Corrected total is the total variability in the response.

The DF column indicates the Degrees of Freedom association with each source of variability, which are independent pieces of information for each source The Model DF is 1 because the Model has one continuous predictor term. So we are estimating one parameter beta sub1. The Corrected Total DF

n-1 which is 14 - 1 = 13. The Error DF is what is left over; it is the difference between the Total DF and the Model DF 13-1 = 12. You can think of Degrees of freedom as the number of independent pieces of information.

The Sum of Squares indicates the Amount of Variability associated with each source of variability.

Mean Square column indicated the Ratio of Model Sum of Squares divided by DF which gives us the average sum of squares of the Model.

The Mean Square Error is the variance of the population. This is calculated by the Error sum of squares by the Error DF which gives the Average Sum of Squares.

The F value is the ratio of the Mean square of the Model divided by the Mean Square for the Error. This ratio explains the variability that the regression line explains to the variability of the regression line that doesn't explain. The p-value is less than

If the p value is less the .05 and we reject the NULL Hypotheses. If the Null hypotheses is true it means the Model with CREATE is not any better than the base. However in this case the Model fit the data better than the baseline model

The third part of the displays Summary Fit measures for the Model

Root MSE - is the Square root of the Mean Square Error in the ANOVA table

Dependent Mean - Average of Response variable for all candidates

Coeff Var - Size of the Standard Deviation relative to the mean

R Square - Calculated by diving the Mean Square of the Model by the total Sum of Square. The R square value is between Zero and 1. Measures the proportion of variance observed in response that the regression line explains

What percentage of variation in the response variable does the model explain? Approximately 30%

Adjusted R Square - This is useful in Multiple Regression

The Parameter Estimates table defines the Model for the data. This provides separate estimates and Significance tests for each Model Parameter. Gives the parameter estimate for the Intercept as

2.16452 (The estimated value of TASK when CREATE is equal to zero) and the predictor variable parameter estimate as 0.06253. If the TASK increase by one unit the CREATE increase by 0.06253 units. We are interested at looking at the relationship between the TAST and CREATE. The p value is to explain the variability of response variable. Since only one predictor variable is used it is equal to the p-value of the overall test. Because the p-value 0.0396 is less than .05 there is significance in variability of TASK

Finally lets enter the results in the equation of Simple Linear Regression

Response variable = Intercept variable + Slope parameter x Predictor variable

TASK = 2.16452 + 0.06253 * CREATE (This is the estimated Regression Equation)

The Graphical Part of the Output

If you have a look at the Fit Plot the shaded area refers to the Confidence interval around the Mean. A confidence. A 95% Confidence Interval gives a range of values which is likely to include an Unknown Population parameter. This indicates that we are 95% confident our interval contains true population mean Y for a particular X. The wider the confidence interval the less precise.

The dashed lines indicate the prediction interval of the individual Observations. This means that you are 95% confident that your interval contains the new observation.

Note that by default Proc Reg displays the Model Statistics in the Plot

How do I store the results in a new dataset instead of printing it?

Use the Proc Reg to write the parameter estimates to Output dataset instead of producing the usual results and graphs. You can then use two options to the Proc Reg statement

- The NOPRINT option suppresses the normal display of regression results

- the OUTEST option creates a output dataset containing Parameter Estimates and other summary statistics from the regression model

References:

http://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/premba/analytical/s7/s7_6.cfm

http://www.stattutorials.com/SAS/TUTORIAL-PROC-REG-SIMPLE-REGRESSION.htm